Kenneth Hince OAM, one of Australia’s pre-eminent dealers in rare and old books, and for many years a music critic for major Australian newspapers, has died peacefully surrounded by family members in Euroa Hospital at the age of 91.

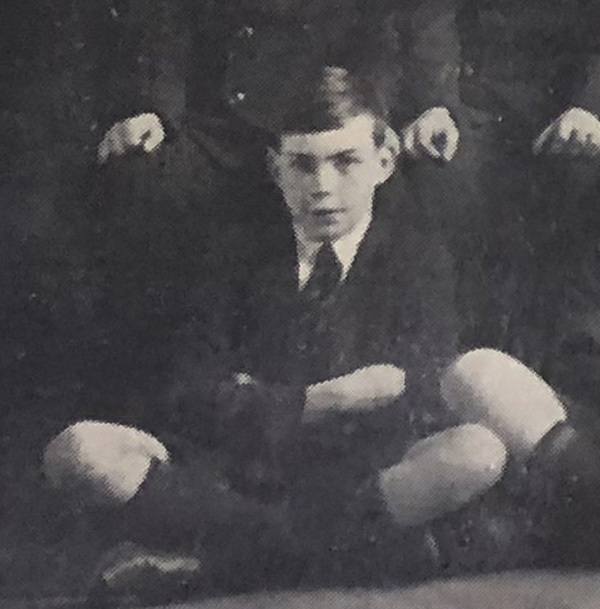

Born in July 1926, Kenneth completed his early schooling at Parade College East Melbourne – the ‘Old Bluestone Pile’ – in Intermediate B Class in 1939. A fellow class member was Ian Fraser, who two years later would be named the inaugural College Prefect (Captain).

In the September ’39 edition of The Paradian, Kenneth, then 13, penned what may well have been his first critique, of his experience in hospital pre and post-surgery.

That 80 year-old critique appears below this tribute.

Kenneth later studied Medicine and Arts at the University of Melbourne, served in the Royal Australian Air Force through the dark years of the Second World War, and later taught languages at Xavier College, before opening his bookshop in Melbourne in 1960.

He then commenced his long and successful career as critic the following year, serving as music critic for The Bulletin (1961-64), the inaugural critic for The Australian (1967-77), and critic for The Age(1977-94).

In 1993, Kenneth relocated to Euroa in Victoria’s north-east, where he established a separate business, Euroa Fine Books. His special literature interests included the settlement and local history of Victoria, the exploration of Australia, art and illustrated books, literature and private press, and general antiquarian.

Kenneth was the principal founder and first President of ANZAAB, the Australian and New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers, and was an honorary life member of that association.

Consequently he was an affiliate of ILAB, the International Association of Antiquarian Booksellers and his authoritative reputation was built on 60 years in the trade.

In 2008, Kenneth was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to the arts – which he told the ABC at the time was due in part to his role in establishing the national antiquarian book sellers association 40 years previous.

“What it has done effectively is to rationalise the practice of old book selling in Australia, and to bring it into line with international practice,” he said at the time.

Kenneth died on February 19 and was privately cremated following a funeral service in Euroa. He is survived by his children Ken, Bernadette, Barbara, Stephen, Monica, Madeleine and Julienne, and 11 grandchildren.

His wife Patricia predeceased him.

In a tribute to his older brother which appeared in The Age, Michael Hince wrote: “He (Kenneth) led a richly fulfilled life of accomplishment which revolved around his close family of seven children to whom I extend my sympathy at their loss”.

“Articulate, urbane and at times a little diffident (a trait he shared with his father) his love of music, the written word and books enriched his life and those of many he came in contact with and influenced,” Michael wrote.

“His achievements in these areas speak for themselves and are well documented.”

LIFE IN HOSPITAL

BY KEN HINCE

(The Paradian, September 1939)

Before I was whisked off by ambulance one bright and sunny Tuesday morning, I had no idea what life in a big public hospital was like. But I was soon to learn.

When I arrived I was taken into a sombre brick building, laid on a high table, and for about half-an-hour was made the subject of an interesting debate between several doctors and students. Finally I was taken to a surgical ward, which was to be my home for the next week.

On arriving there I was examined by a few more doctors, and to my surprise I learned that I was an ‘acute’, and was to be operated on at about 2.30 the same day. Right on time I was wheeled out of the ward on a trolley, dressed up like a circus clown, and into the theatre, and looking into a huge lamp above the table, was just in time to see a nurse preparing to take me by surprise with a pad and a spray, reflected in it. I seemed to just fade to nowhere.

I will draw a curtain over the next two days until I was well enough to take much notice of my surroundings.

The ward was a long, narrow room with 133 squares in an oblong roof. I had plenty of time in which to count them. The first thing I would see on walking, generally, was a nurse pushing round an auto tray containing breakfast for the ward.

The only breaks of the general monotony of hospital life were the two mails at 9.30 and 2.30. I received 17 letters in that seven days that I remained there, and that, according to some other patients, was a record.

Today the only reminder that I have of life in hospital is a small scar, and I am thankful for this, for on the whole, hospital life is very depressing.